IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS

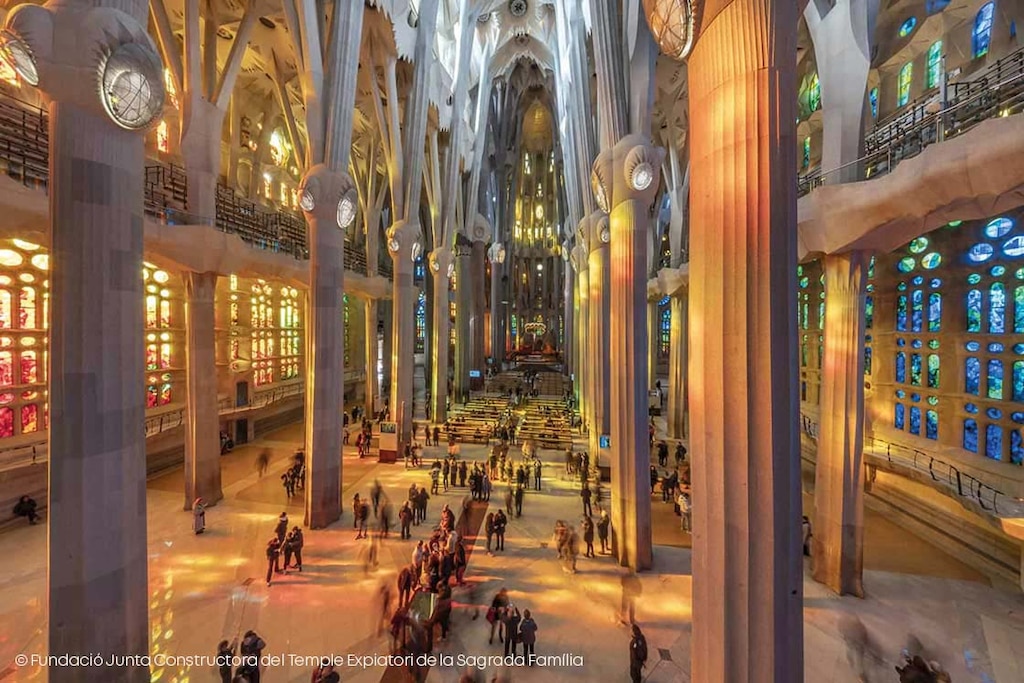

Located in the heart of Barcelona, the Sagrada Família is not only one of Antoni Gaudí’s masterpieces but also a monumental construction and logistical challenge. Gaudí’s unique interpretation of Christianity, nature, geometry and the world produced a design as complex as it is innovative. As a result, generations of engineers, architects and artisans have had to reinvent construction techniques and logistics processes.

The logistics behind the Sagrada Família are highly sophisticated. The basilica — which stands in one of Barcelona’s most densely populated neighbourhoods — welcomes over four million visitors annually and still functions as an active place of worship. “To coordinate neighbourhood life, tourist flows and religious activities alongside construction, we zoned the work areas,” says David Puig, Assistant Architect. The Sagrada Família is organised so that active construction zones are clearly marked. Paths for visitors, parishioners and workers do not intersect, and tasks that occur in the same space are scheduled at times that do not interfere with worship or public access. “Many stages are completed off-site in workshops. We also comply with the regulations in force and the working hours set by the municipal licence to minimise disruption for local residents,” says Puig.

Over 140 years under construction

Since the first stone was laid in 1882, the Sagrada Família has been in a state of constant flux. What began under the direction of Francisco de Paula del Villar was reinterpreted a year later by Antoni Gaudí. The latter conceived a radically different project destined to become both a Barcelona landmark and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Since then, its construction — and the intricate logistics operations supporting it — has continued to evolve.

Puig says: “Technologies have revolutionised our processes. In many cases, they’ve brought to life ideas that Gaudí had already envisioned or begun.” One of the hallmarks of his method is that the interior geometries evoke shapes found in nature: straight lines are arranged to create the illusion of undulating columns and walls. “To carry out such a complex geometric project, two-dimensional plans weren’t enough for Gaudí; he needed to work in three dimensions using plaster models.” Today, digital modelling through CAD and BIM programs (specialised in architectural design and 3D simulation) has simplified both the design and execution of the project.

Since its early days, the Sagrada Família’s logistics processes have balanced construction, worship, and the flow of millions of visitors

Gaudí began the Sagrada Família with the crypt and the apse wall, employing traditional methods: small stones and manual adjustments by stonemasons. However, in the final stage of his life, while working on the Nativity Façade, he introduced innovative materials for the time (e.g. concrete in the upper sections) and utilised prefabricated elements. “Today, we follow the same logic, prefabricating and assembling as many pieces as possible to simplify work at height,” says Puig. When completed, the basilica will surpass Germany’s Ulm Minster — the current world record holder at 161 metres high — by 11 metres.

Material supply

Initially, Gaudí used sandstone from Barcelona’s Montjuïc mountain. Highly prized by architects, this sedimentary rock stands out for its superior strength compared to other varieties and for its wide range of colours: light grey, greenish grey, beige, yellow, ochre, gold, purple and reddish tones.

However, when construction of the Passion Façade began, the shortage of Montjuïc stone became evident. Shortly afterwards, quarrying was abruptly and permanently halted. “We haven’t found a single rock that offers the same array of colours, which is why we use similar stones from different countries, including Germany, France and the UK,” says Puig.

Stones from Germany, France and the UK are delivered to the Sagrada Família through an international logistics network

The scale of the project, limited space on the site (increasingly occupied by the construction itself) and the constant flow of visitors led the Construction Board to implement its own logistical system. The solution was to move much of the work off-site: elements are prefabricated in external workshops and only transported to the basilica for final assembly. This was the case, for example, with singular pieces like the star atop the Virgin Mary Tower and the cross that will crown the Jesus Christ Tower; these works were crafted in specialised facilities before being transported and assembled in Barcelona.

The Sagrada Família’s logistics processes are organised in phases:

- Raw material arrival. Workshops receive raw inputs (such as stone) and sort them for further processing.

- Manufacturing. Specialists craft components according to the architects’ specifications.

- From individual pieces to large modules. Prefabricated elements are assembled into larger units.

- Installation in the basilica. Finally, the finished modules are transported to the site and placed in their final positions.

The team behind the Sagrada Família

The Sagrada Família’s complex logistics processes also rely heavily on people: behind the materials and technology, a well-coordinated human network keeps everything running. “We have around a hundred professionals dedicated to three main areas: the architectural project, construction and basilica management. This is complemented by collaborations with external companies,” says Puig.

The architectural team is responsible for developing and keeping alive Gaudí’s vision: interpreting his design, adapting it to modern times and maintaining coherence. This core group is supported by external engineering firms for highly specialised tasks, such as structural calculations.

Many of the pieces for the Sagrada Família are made in external workshops and arrive ready for assembly in the basilica

Regarding construction, the in-house department verifies that all work is carried out in accordance with the technical documentation. One of its main roles is to create the foundational infrastructure. This involves preparing and organising logistics operations to enable external contractors to carry out their tasks safely and efficiently. The department then hires and coordinates the contractors responsible for specific parts of the project.

Finally, the management team oversees all aspects of the basilica’s operation: from religious services and cultural visits to communications and ensuring a positive experience for the millions of annual visitors.

Build, preserve and restore: The logistics behind a living temple

The Sagrada Família is approaching its final stretch. “It’s at a very advanced stage,” says Puig. For years, 2026 was cited as the symbolic completion date, coinciding with the 100th anniversary of Gaudí’s death. Nevertheless, the pandemic forced a revision of the timeline, pushing that horizon further out.

Over nearly a century and a half, several factors have prolonged the project. Gaudí’s complex design posed unprecedented technical challenges, and his sudden death left the work without its main driving force. The Spanish Civil War added further setbacks, damaging parts of the building and destroying original plans and models. This made it necessary to study and reconstruct the modernist genius’s legacy.

Meticulous logistics operations enable the Sagrada Família to be built, preserved and restored simultaneously

Funding has also been a critical issue: from the start, this expiatory temple has relied on private donations and the contributions of millions of visitors. That means every economic crisis — and most recently, the drop in tourism during Covid-19 — has caused delays and interruptions.

“Beyond what remains to be completed, maintenance, restoration and conservation work are all ongoing,” says Puig. Today, the Sagrada Família is both an unfinished masterpiece and a space that is never idle: it is being built, preserved and restored simultaneously. Behind it all is a logistical machine that has supported a project spanning generations.